Domestic

livestock is not the major cause of loss of wild mammals.

We

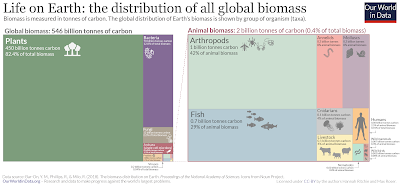

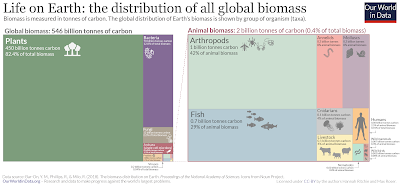

have all seen it, the graph showing that just 4% of the world’s mammals, by weight, are

wild; humans

account for 36%, and livestock for the remaining 60%.* It is certainly

deplorable that there are so few wild mammals. Most people using these figures

and probably most people hearing them, draw the conclusion that domestic

livestock has squeezed out wild animals. But that is a far too simplistic conclusion.

This is demonstrated both by large-scale top-down analysis and smaller scale

empirical evidence.

To begin with crop lands occupy 1.5 billion hectares

and around 1.6 billion hectares of grasslands are

effectively grazed by domestic livestock. This makes up 3.1 billion hectares out of a total of

14 billion hectares. Excluding barren lands (glaciers, rough mountains)

agriculture occupy “just” one third of total land area (which is of course

already a lot and perhaps too much).** Land-use can affect a bigger area then

it physically occupies, but clearly agriculture, whether cropping or grazing,

can’t be the main reason for why there is so little wild life in the 7 billion

hectares of “habitable” land which are not under agriculture management.

On a temporal scale, the decline of wild mammals often

predates agriculture expansion. This is apparent in the late Pleistocene megafauna

extinction taking place more than 10,000 years ago, well before agriculture and

domestication of livestock. There are still heated arguments over if hunting by

humans or climate change was the main cause, most likely they were combined. Some researchers have estimated that the total biomass of herbivores,

approximately a billion large bodied mammals, at that time equaled current biomass

of domestic animals. Regardless of the exact numbers it is apparent that the

total weight of wild mammals shrank considerably by this “event”, and that

mammal wild life hasn’t recovered since.

Finally, by using data for the total global primary

productivity (the net

photosynthesis so to say) one can see that of the total net primary production,

humans and their livestock “appropriate” around 20 percent for agriculture

purposes. This is of course bad enough, but it still means that there is

biological space left for many more mammals and other wild life.

*

Even if cattle, wheat and corn now grow where bison

previously roamed in North America, I have seen no convincing evidence that

that the extermination of bison was driven by agriculture expansion, but rather

by a combination of hunting, disease and indirect

effects caused by the decline in Native American populations and abilities to

manage the bison herds. Obviously, the

enormous expansion of both croplands and ranching in North America would have

collided with a bison herd of 60 million head, sooner or later. But cattle and

bison can co-exist: according to a study from Utah there is more competition between cattle and

jackrabbits than between cattle and bison when they share the same

resources.

The massive death of >500 million ungulates in Africa in the late 19th century i which both

domestic and (mostly) wild animals were victims was caused by Rinderpest, a

disease brought in by cattle from India. This could in some way be seen as

caused by “agriculture” in a wider sense, even if it was more a function of

humans moving animals around than agriculture as such as domestic cattle

already were all over Africa.

Research in Kenya show a certain level of competition

between cattle and small herbivores but not with bigger herbivores. The researchers suggest: “that interactions between livestock and wildlife

are contingent on rainfall and herbivore assemblage and represent a more richly

nuanced set of interactions than the longstanding assertion that cattle simply

compete with (grazing) wildlife”. Studying the populations of domestic cattle

and wild life in Northern Tanzania for 17 years, researchers concluded that while there was a high density of cattle and sheep

and goat “several wildlife species occurred at densities similar (zebra,

wildebeest, waterbuck, Kirk's dik-dik) or possibly even greater (giraffe,

eland, lesser kudu, Grant's gazelle, Thomson's gazelle) than in adjacent

national parks in the same ecosystem.” Research from South Africa shows that there is some competition between oribi

antelope and cattle. Cattle facilitate oribi grazing during the wet season

because cattle foraging produced high-quality grass regrowth. Despite this, they

found that “cattle foraging at high densities during the previous wet season

reduced the dry season availability of oribi's preferred grass species.”

In Sweden the number of wild animals have increased tremendously the

last 200 years. In the mid-19th century there were

just a few hundred roe deer, moose and red deer and now there are around

300,000, 240,000 and 26,000 respectively. Wild boars were exterminated in the

17th century and now there are some 350,000. Beavers were gone by 1870 and now

we have 100,000. Hunting of cranes and swans have just started again as their

numbers are causing problems for farmers. Even the predators are making

comeback. Meanwhile, the number of people, pigs and poultry has increased many

times. The acreage of arable land peaked in 1916 and the number of cattle

increased with 50% from 1866 to its peak 1936, after which it fell back to

levels lower than in the 19th century. This remarkable comeback of wild life is a result of many factors but

hunting regulation is the most important one.

Researchers studying the dynamics of domestic and wild herbivores in Norway conclude that total herbivore biomass decreased from 1949 to a minimum

in 1969 due to decreases in livestock biomass. Increasing wild herbivore

populations lead to an increase in total herbivore biomass by 2009. “Declines

in livestock biomass were a modest predictor of wildlife increases, suggesting

that competition with livestock has not been a major limiting factor of wild

herbivore populations over the past decades.” There has been a “notable

rewilding” in Norway. They conclude that “Norwegian herbivores remain mostly

regulated by management”, most notably hunting.

For fisheries and whaling the role of hunting and

overexploitation is even more obvious than for the land living animals.

For sure, there are many cases where the expansion of

farming causes habitat destruction and loss of wild life. The 2022 global Living Planet Index shows an average 69% decrease in

monitored wildlife populations between 1970 and 2018. A team of researchers studied the causes

for threats to 23,271 species, representing all terrestrial amphibians, birds

and mammals. The six major threats were agriculture, hunting and trapping,

logging, pollution, invasive species, and climate change. Their results show “that

agriculture and logging are pervasive in the tropics and that hunting and

trapping is the most geographically widespread threat to mammals and birds.

Additionally, current representations of human pressure underestimate the

overall pressure on biodiversity, due to the exclusion of threats such as

hunting and climate change.” Exactly how agriculture

threatens wild life is not made clear in the study.

The impact of farming depends a lot on the context,

which environment, which species of wildlife and of livestock respectively as

well as management. How we farm,

trade and eat is of critical importance: “In short, the impact of food

production on biodiversity arises not from a single fault, but from the nature

of the system as a whole”, according to a recent report by UNEP, Chatham House and Compassion in

World Farming.

When land is cleared and plowed and converted into

cropland most of the original flora and fauna will vanish from the place and a

few new ones will enter. By and large, crop farming and wild life are no good

mates, so there is quite a direct link between cropland expansion and reduction

in wild life. There are many things farmers can do to make cropping more

biodiversity friendly, but grazing animals, boars and other mammals will not be

welcome in croplands as little as grasshoppers or lice are.

For grasslands the story is quite different. If a

tropical rain forest is razed to provide grazing for cattle, biodiversity and

wild life till be harmed to a very large extent. But most grazing in the world

takes place in lands that have either been natural grasslands or which were

converted (or restored) to semi-natural grasslands since many centuries or

millennia (which is the case of many of Europe’s grasslands). Grazing animals can co-exist with many other mammals and the share of primary productivity that humans and their livestock take from

grasslands is much smaller than from croplands, where we take almost all. The biggest conflict is with predators even

if there are many examples of how domestic livestock can co-exist with

predators.

Some make the case that domestic livestock, in particular cattle, to

some extent can act as ecological replacement for now-extinct megaherbivores

and that they can maintain landscapes and functions that otherwise would be

lost (see for example here, here and here).

|

One of our cows in our silvo-pastoral lands. Photo: Gunnar Rundgren.

|

There are, obviously, many things farmers can do to protect

and promote wildlife. But that would be the subject of another set of articles.

You can find some examples here

and here.

For sure, the cow and the deer can easily co-exist. On our farm, there is plenty of wild-life co-existing with our small herd of five mother cows. There are deer, elk, boars, fox, voles, fox, the occassional lynx a huge number of birds including flocks of gees, cranes. In the grassland they all thrive and do little harm, in my field of vegetables, I chase them away.

*Interestingly, the weight of

arthropods is ten times more than the weight of livestock and the weight of all

the organisms in a living soil is much higher than any animals grazing on the

land.

** Many quote considerably higher

numbers, e.g. Our world in data. They classify almost all global grasslands as

grazing area for domestic livestock, but that is simply not correct. It is only

a minor part of the grasslands that are actually grazed. For a detailed

analysis see the supplement of Climate warming from managed grasslands cancels the

cooling effect of carbon sinks in sparsely grazed and natural grasslands by Jinfeng Chang et al (2021).